📌 Hot Take: I Always Plan for Self-Ended When Paginating

Yes, that requires tougher text choices--and, for me, that's the point.

Pagination (and the related page turns) are such essential elements to consider when writing picture books that I don’t think I need to sell any serious creator on those points. Still, when I was starting out, I was so confused about how to do this!*

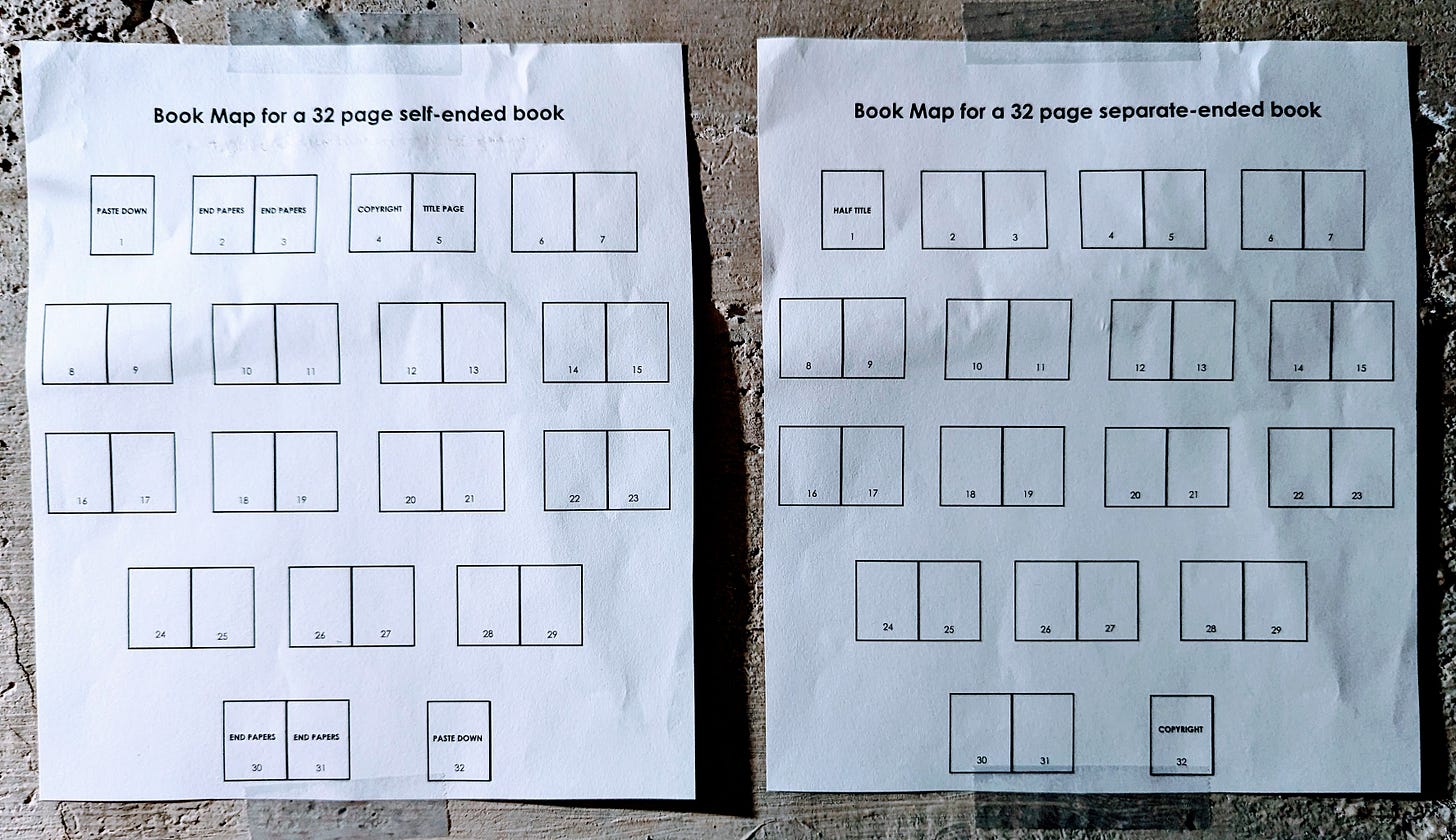

Typically**, there are 32 pages in a picture book—but even in that, there are two main “flavors” of picture books: self-ended (meaning the signatures themselves are used to bind the book to the cover) and separate-ended/colored-ended (meaning special endpapers secure the book to the cover, most often using a specialty colored paper called RAINBOW®). Separate-ended picture books contain (roughly) two-and-a-half-or-three more spreads for text than self-ended ones; however, self-ended picture books include two sets of four-color printed endpapers (nothing to sneeze at—especially when, as I do, you love illustrated endpapers and think they help suck a reader immediately into the story).

If you still aren’t clear on identifying which is which, author-illustrator Jim Averbeck does a great job of “showing” the differences between self-ended and separate-ended picture books in this five-and-a-half-minute video, using real picture books as examples.

SO…between the (main) options—one that contains roughly 12 text spreads and one with approximately 15 text spreads—which do you think most authors seem to plan for? (SHOCKER… it’s the one with the most text spreads!) 😂 There’s nothing inherently wrong with that—plenty of publishers happily use separate-ended books, even if they are the more expensive format. Still, I think sometimes we writers look to be more expansive—rather than economical, as poetry is—in our picture-book-writing out of, and I say this lovingly - maybe (SOMETIMES) just a little laziness and/or falling in love with every word we type instead of the story always calling for it? - which is not always ideal for a particular story’s pacing nor the visual “space” left for an illustrator’s storytelling.

Instead, nowadays, when I paginate—I plan for self-ended. I would rather prepare for fewer text spreads and have the story work great (and be pleasantly surprised if we get some bonus spreads!) than vice versa. Also, many editors I have had the pleasure of chatting with use self-ended as their default, as it’s more economical and allows for four-color printed endpapers. (What does four-color printed endpapers mean? It means if you envision full-color illustrated endpapers, or to have essential story elements being part of the endpapers, you will want to plan for self-ended because colored papers are typically not printed. And, when they are—the color palette for printing is limited to only one or two color endpaper printing because RAINBOW® is screen printed—which also requires extra production funds. And if you’re lucky enough to have your book come out in other editions—say paperback—separate-ended end papers will be dropped, anyhow, then, so you never want to put essential visual information on them, regardless.)

Because I LOVE printed (esp. full color) endpapers, and I want the barriers to an editor acquiring my book to be as minimal as possible (I’d rather them use that money for getting a fabulous illustrator or doing something cool with the cover!), I whip my stories into shape using the more streamlined self-ended pagination format. Of course, that doesn’t mean I can't change my mind if my story truly doesn’t work with fewer spreads! And it doesn’t mean my process should be yours!

HOWEVER, if you are only ever using relatively-luxurious separate-ended pagination and your story isn’t getting the “bites” you expected, I think it’s worth investigating repaginating your manuscript as self-ended. The svelter “usable” page count for text spreads will force you, at least as an exercise, to cut the least essential/compelling spreads and/or scenes—and could help you significantly with pacing. (In my eyes, those are two major reasons to at least try it!)

* Here’s the prerequisite disclaimer: “If you are author-only, you don’t need to submit your paginated version.” Still, I think you should do this as part of your practice for YOURSELF, as it definitely helps with pacing and revision. And, at least for my submissions, while I don’t include page numbers, I like to use the old “double enter key” trick to show where I envision page turns. Sure, the choices will not be mine to make—still, I like to think including this shows the thought I’m putting into my work—and into pacing and page turns.

** There are, of course, other options if your story truly needs them! (Chronicle Books is particularly flexible in this regard, I’ve noticed—sometimes adding half signatures—meaning four pages instead of eight, even. 🤯) But 32 pages is what they call “industry standard,” and I think it’s wise to start with that.

*** You can learn more about paginating on Tara Lazar’s well-bookmarked blog resource page or on Debbie Ohi’s similarly beloved-for-good-reason templates page. Hilariously, when I redid Tara’s “pull seven books off the shelf and see their construction,” ALL of mine were self-ended (the opposite of what she found)! Maybe self-ended picture books have become far more common than in 2009, when she wrote the post? Or perhaps we both just have very different picture book shelves! So funny, though—check your bookshelf and see what you find!

Your friend who likes to spread her work out,

Elayne

My posts are always free, but my focus isn't; if you found this post interesting or useful, please consider ♡' ing it so I know. Thank you!